Voices from thefrontlines

Climate change is reshaping our world and exposing Africans, across the continent, to increased hardship. How can its people be empowered to face climate shocks and stressors and make informed decisions to move or stay now and in the future?

On the forefront • 4.1

PastoralWays

PastoralWays

Herding communities face an uncertain future

Introduction

Pasturelands will see big changes due to climate disruption. Livestock herders could be forced to embrace not only new routes but also new ways of life.

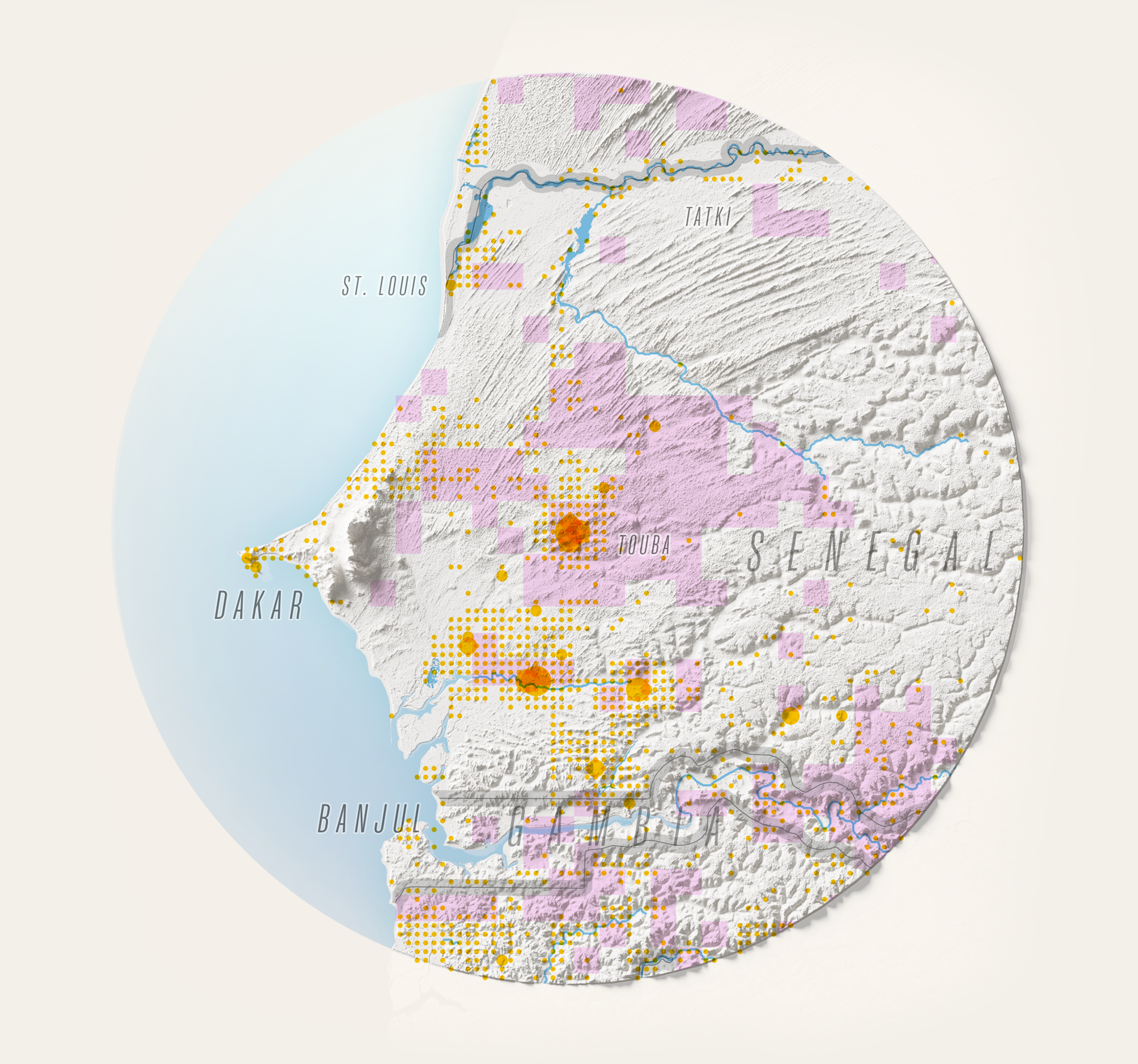

Droughts could force traditionally mobile communities – including 300 thousand pastoralists in Senegal – to seek stability and settle beyond their usual grazing lands. In the east of the continent, the number of people moving away from pastoral areas could be even 10 times greater than in the west.

Tatki District, Senegal

Demba Ly (21), pastoralist

Ly is a young Fulani shepherd. His herding stick is part of an ancient tradition, a talisman that offers spiritual protection. He is unsure of his future, though, and like many of his generation, may have to embrace a new way of life.

Sheikh, Somalia

An unnamed shepherd

Drought has made nomadic farming hard for many shepherding farmers in the Horn of Africa. Livestock are dying as traditional grazing areas lose natural forage. Some families are settling into different farming practices or taking off-farm work.

Traditionally mobile livelihoods disrupted

Pastoralism is the main livelihood of about 268 million people across Africa. In dryland areas, it is often the most viable livelihood, if not the only one. For many generations, livestock herders have created economic value from scarce natural resources, while also maintaining ecologically fragile ecosystems.

However, pastoral communities and livelihoods experience growing pressure, and not just from climate change. They face increasing stress from competing land uses, surging demographics, insecurity and hardening border regimes, poor governance of natural resources, and the marginalising of pastoralists from public services and political processes.

Climate change adds to these challenges as it threatens the health, value and survival of their herds and makes it more complicated to access water and grazing lands. By narrowing pastoralists’ options for mobility, climate stressors threaten to drive herders into more frequent conflict with other pastoralists or farming communities

Some pastoralists cope by moving differently, settling more, and adopting technology

In Senegal, pastoralists change their movement patterns in response to changing weather and climate conditions. Young people cope by taking up seasonal work in farming or urban areas. When resources become harder to reach, herders use modern technologies to cope. They transport water and fodder to where their herds are or use vehicles to move the animals around. Some herders combine nomadic life with farming. This partially sedentary approach – agro-pastoralism – can boost their income and their resilience to climate change. However, adopting new herding routes or settling down can split up families, increase the household burden on women, and expose families to insecurity.

When herders decide to settle, it may not always be voluntary. They may be forced to become sedentary as a result of livestock losses caused by disease, drought, or flooding, or by policies that limit their ability to move.

Tatki District, Senegal

Collecting water and firewood is the women’s task in many African herding communities, while men tend to the animals. For Fulani women in northern Senegal, it could mean travelling increasingly longer distances as the environment degrades.

Tatki District, Senegal

Different farmers’ flocks mix at a watering hole as the animals jostle to drink. Shepherd Samba Ly (62) checks that all his animals are accounted for. As more pastoralists settle down to farm, tensions with those who remain herders may arise.

Tatki District, Senegal

Animals are central to Fulani culture, whose livelihood has evolved alongside their herds in this tough, dry environment. Generations of pastoralists have cared for fragile drylands and created value from the land in spite of its scarcity.

Tatki District, Senegal

Bringing the herds to water points during the rainy season is a social occasion. Pastoral communities across the continent will see dramatic change as climate impacts make some areas more suitable for herding, while others become too dry.

Tatki District, Senegal

Every three months, Fulani herders check their flocks for sickly animals, and treat them for common parasites and diseases. Pastoralists will have to cope with more livestock deaths and price shocks caused by diseases and heat stress.

Feteh Doundou Settlement, Senegal

The village is far from the mobile phone network, so people often hang their phones high up to get reception. Herders are adopting new technologies as conditions change, including using vehicles to bring in water or fodder for their herds.

Feteh Doundou Settlement, Senegal

Fulani men huddle around a mobile phone to catch up on family news. As some herders use partial settlement — agro-pastoralism — to adapt to climate change, families become separated.

Feteh Doundou Settlement, Senegal

Fulani herder and clan leader Samba Ly (62) is surrounded by his grandchildren. Sharing traditional knowledge across the generations, a mainstay of Fulani culture, risks becoming obsolete with climate change.

Feteh Doundou Settlement, Senegal

Fulani families that have settled into sedentary farming practices enjoy more regular access to facilities and healthcare in nearby towns. Families are growing bigger, a sign of prosperity in their culture.

Tatki District, Senegal

Herders traditionally take their animals to water. Now, many fill containers at wells — like this one, 3 km from the village — and transport it home. As climate stress intensifies, managing shared water and land could test social cohesion.

Loss of heritage and identity

For centuries, African pastoralists have drawn on intangible heritage to build their resilience to climatic variability and to support adaptation practices. Pastoral communities have recorded their experiences as memories that are passed down through generations and have been translated into a range of adaptive practices. However, changes to their traditional routes and the distances travelled to move cattle between grazing sites are affecting the effectiveness of this handed down knowledge. Climate change thus risks making traditional knowledge obsolete. The implications of these changes go far beyond the loss of pastoralists’ material resources, threatening a loss of heritage that could also erode family structures, marriages, cultures, religions, and polities.

Climate mobility may reshape the demographics of pasturelands

The analysis of climate mobility dynamics in pasturelands in West and East Africa shows both population gains and losses. Under low emissions scenarios, climate mobility into pasturelands is relatively high. However, in the High Road scenario, up to 3 million people are projected to leave pastoral areas by 2030, and 7.6 million by 2050. The Rocky Road scenario projects greater out-mobility of 8.7 million people by 2050.

In the parts of West Africa where pasturelands are suitable for animal grazing, climate mobility could add between 250,000 and almost 2 million people to the population living in pasturelands. Senegal could see up to 380,000 people migrating away from pastoral areas by 2050 under the Rocky Road scenario. Meanwhile, pasturelands in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are forecast to see smaller increases in population of 163,000 and 64,000 people respectively under the Rocky Road scenario

East Africa: Large population shifts

In East Africa, pastoral areas could see a net population loss of as many as 1 million people by 2050 due to climate stressors. Rwanda and Sudan will see the highest population decreases, with around 3 million people moving out of pasturelands in Rwanda under the High Road scenario, and 1.5 million people forecast to leave Sudan’s pastoral areas under both the Rocky Road and High Road scenarios. This is likely to be in response to drying trends. Pastoral areas in Eritrea and Somalia could see smaller population declines. However, in Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Sudan, pastoral lands are projected to see more people moving in as climate conditions become comparatively more favourable. Ethiopia is forecast to see the largest increase in population under the Rocky Road scenario, with around 280,000 people expected to move into its pastoral areas by mid-century.

Figure 1

Internal climate mobility will be significantly greater and less balanced in pastoral areas in East Africa compared to those in the west of the continent.

Internal climate mobility by 2050 in pastoral areas under the Rocky Road scenario

Arriving

Leaving

Source: ACMI Africa Climate Mobility Model, 2022

The Way Forward

Supporting pastoralists with climate services and early warning mechanisms can help them adapt to shifting weather patterns and climate shocks.

Diversifying herds, for example by introducing camels in drying areas, can increase resilience. Livestock insurance products and better decentralised infrastructure serving people and their herds also help. Locally anchored and regionally coordinated mechanisms that anticipate and mediate possible conflicts between different users of land and water could mitigate the risk of displacement and destabilisation. Most importantly, pastoral communities must be given a voice and stake in envisioning and planning for how to adapt to a future of climate disruptions. They must be engaged in developing a blueprint for how their lifestyles and traditions can be part of a just transition.